Accommodate or Fail:

The Business Case for Universal Design

Across online and digital platforms, and in the built environment we continue to see the importance of user-centered design.

The benefits of a positive user experience lead to customer loyalty, employee retention, higher conversion, and increased productivity.

It is not the individual that should be adaptable or able-bodied, it is the product and environment that must be. And the more users you can accommodate for, the better your results will be. The business case for universal design is clear on many levels:

In 1990, OXO tripled the cost of innovated kitchen utensils (a Good Grips potato peeler cost about $6, compared to $2 for a conventional peeler) that were specfically improved for consumers with arthritis, and by 2004 they were so successful that they were acquired for $273.2 million¹. Online, the Legal & General Group saw a 25% traffic increase within 24 hours of making their website accessible, growing to 50% eventually². In the workplace, employees leaving their jobs in masses as part of what’s being called The Great Resignation exposes the lack of accommodation and disconnected of values between employees and employers during the COVID19 pandemic³.

So how do we design for loyalty, retention, conversion, productivity? Using universal design principles.

What is universal design?

In a nutshell, universal design is the practice of designing an environment so that it can be accessed, understood and used to the greatest extent possible by all people regardless of their age, size, ability or disability.

I was privileged to work with Amy Pothier, a wizard of an Inclusive Design and Building Code Strategy who led an entire practice area with accessibility at its core. We developed new ways to communicate the principles of universal design, which each call for an integration of inclusivity in the design process to promote independence and autonomy.

Our work included illustrative handbooks, checklists, and guidelines for tech giants with a focus on how their workplaces can be designed for accessible use. This case study examines the need to universal design, how it has evolved, what to expect, and how to design for it.

Who benefits from universal design?

In short, everyone. On a basic level, it is important to understand this is not a special requirement for the benefit of only a minority of the population. It is a fundamental condition of good design. If an environment is accessible, usable, convenient and a pleasure to use, everyone benefits. By considering the diverse needs and abilities of all throughout the design process, universal design creates products, services and environments that meet peoples' needs.

On a societal level, rates of disability are increasing, due to population aging and global increases in chronic health conditions⁴. More than one billion people in the world experience some form of disability - that’s about 15% of the global population.

It is also crucial to understand that disabilities are of different severity, can be visible and non-visible, and may come and go. We are not just talking about individuals in wheelchairs, it’s also people with learning disabilities, mental disorders, brain injury, hearing impediment, chronic health conditions.. the list goes on.

A brief history.

Modern society has continued to recognize a progressive responsibility to be inclusive. Prior to industrialization, most families had immediate experience in coping with disability - communities and churches managed life-circumstances, nutritional deficiencies and lack of medical attention were not uncommon, and risky occupations present challenges to many people. The urban environment brought standardization, which meant homes and amenities were generally built for the “average” consumer instead of the individual. This led to heightened awareness of the need for change, and activism which brought reform.

-

Organized activism begins after journalist Nellie Bly exposes horrid conditions faced by people with mental conditions, who were viewed as objects of pity, requiring charity rather than accommodations to live independently.

-

A group of young adult New Yorkers form an advocacy group during the Great Depression, specifically for employment for people with disabilities.

-

Disabled WWII veterans in the 1940s and 1950s, with the support of a national audience of thankful citizens, placed increasing pressure on government to provide rehabilitation and vocational training.

Between 1960 and 1963, President John F. Kennedy organized committees on the research and treatment of disability.

In 1961, The American National Standard Institute published its first standard for accessible design:

-

fter years of activists lobbying Congress, civil rights of people with disabilities were protected by law for the first time in history

-

After decades of campaigning and lobbying, the ADA was passed to ensure equal treatment and access of people with disabilities to employment opportunities and public accommodations.

-

A working group of architects, product designers, engineers and environmental design researchers, led by the late Ronald Mace in the North Carolina State University, challenge the afterthought-approach to accessibility by releasing a guide:

-

Edward Steinfeld and Jordana Maisel publish a much-needed reference to the latest thinking in universal design.

How can universal design be implemented?

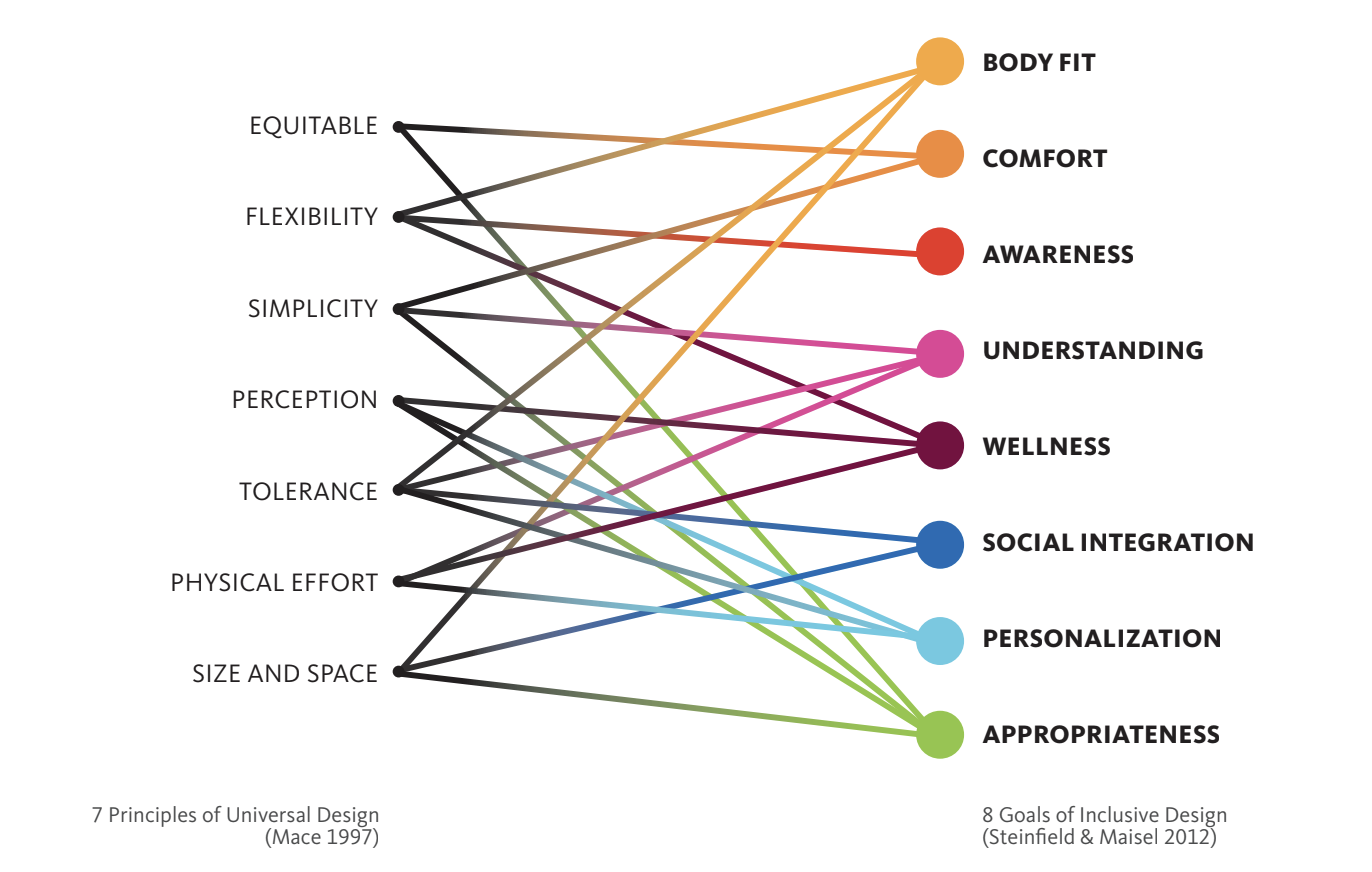

In alignment with Steinfield & Maisel’s 8 Goals of Inclusive Design, integrating the following principles will help achieve best practices in universal design:

-

Passive and active methods to address the range of body sizes and abilities

-

Low physical effort to operate spaces and devices helps all.

-

Safely understand and navigate spaces.

-

International symbols, legibility, colour and contrast.

-

A universal concept that promotes a healthy and safe environment.

-

Consider everyone in designing social spaces.

-

User control and choice for personal and group spaces.

-

Consider cultural values and context in all experiences.

Using graphics to inform universal design.

To effectively demonstrate how policies, standards, and strategies are best practiced, it takes plenty of integration - specifically, in my experience, collaborative efforts between brand, technical, and consultant teams - to communicate code requirements.

The solution for several projects that I worked on was using versatile flat design assets and applying brand palettes accordingly, in conjunction with axonometric diagrams, floorplans, and custom icons.

Footnotes

¹ Samuel Farber, developer of kitchen utensils, dies at 88 (June 2013)

² The Business Case for Digital Accessibility (July 2005)

³ The Great Resignation: It’s time to meet employees where they are (November 2021)

⁴ Disability and Health (November 2021)